Katleen Vermeir

- AMBULANTE ARCHITECTUUR

- AXIS MUNDI

- BELLE-VUE

- CADAVRE EXQUIS (BRUSSELLE, PART1)

- CIRCUITS

- DIACHRONICAL LANDSCAPE

- FITTING THE PICTURE

- HORTUS CONCLUSUS

- LIQUID ARCHITECTURE

- NO MAN'S LAND

- SEISMOGRAPHIC REGISTRATION OF A BUSRIDE DURING A LANDSCAPE

- TABLEAUX-VIVANTS

- TABLEAUX-VIVANTS (after Vermeer)

- TABLEAUX-VIVANTS (CONSTRUCTION MODELS)

- TABLEAUX-VIVANTS/ CONSTRUCTION (MODELS) #04

- THE HISTORY OF NEW YORK (FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE WORLD TO THE PRESENT)

- THE IDEAL CITY (PORTRAITS)

- THE IDEAL CITY (TWO BOATS)

- THE PASSING OF A PERFECT DAY (for GM-C)

- THE PASSING OF A PERFECT DAY (REVISITED)

- WATERDRAWING

- WHEN DID YOU LAST MOVE YOUR FURNITURE AROUND?

SUGGESTION AND EXPERIENCE. ABOUT THE CONCEPT OF SPACE IN THE WORK OF KATLEEN VERMEIR.

Architecture is all about managing space. Architects however are no longer the only ones working with space - more and more contemporary artists venture into this domain, but the purpose of their practice is quite different: whereas architects manipulate space for a certain (functional) purpose, installation artists use space in order to express something or to bring about a certain experience with the visitor. Katleen Vermeir (1973) is such a 'space artist'. She uses space to examine the phenomenon of time in all its dimensions. This could mean she makes the passing of time tangible, but just as well that she maps the history of a place or helps a memory to materialize. The link between these spatial and temporal dimensions is always the human body.

In the last century, the way we think about space and how we deal with it, has changed thoroughly. Until the end of the 19th century the notion of space was based on a material interpretation: the emphasis lay on its physical delimitation. Vermeirs installation ‘Ambulante architectuur’, at Netwerk Galerij in Aalst (1999), explores the boundaries of this traditional concept of time. Here, the artist reconstructs the first blueprint design of the gallery (which was created by joining two small working-class houses) as well as the renovations that were never realized, by using black elastic thread and aluminum capillary tubes. Vermeir thus creates a delicate web of contours, inciting the visitor to start a spatial discovery that leads via apparent door openings, windows and partitions to the gallery’s past, present and future. This way, the visitor develops a spontaneous and peculiar choreography in which he obtains a spatial insight through his own bodily presence. This complex perception arises without any form of technology: with a few simple threads an intensive suggestion of the architecture is created. With this installation KatleenVermeir illustrates how little you sometimes need to bring about strong spatial experiences and physical sensations.

By concentrating on the spatial experience rather than on the delimitation of space, Katleen Vermeir joins the phenomenological concept of space which modernity introduced at the beginning of the 20th century. In this period, architects wanted to bring about spatial sensations rather than design spaces. They hereby manipulated the way we observe a space, and added the dimension of time. Variations in the intensity of the light, in sounds, scents and colors add an inherent temporal dimension to the room, and give the impression that the space moves around the visitor. Katleen Vermeir uses this effect in her series of Tableaux vivants. Here, groups of people assume a pose for a short period of time, with a landscape or a townscape as a background. The attire of these observers is plain, but expressive by its color. The change in the shadows, cloud movements and range of coloring in the background brings a dimension of time in these video paintings. This passing of time however seems to have no impact on the observers. The participants in these Tableaux vivants are after all no actors who do things or express emotions, but abstract figures reminding us that the human measure remains our only, invariable reference in a continuously evolving world.

The idea of permanent dynamics applies especially to our cities and landscapes: they are no static entities, but evolving systems. Throughout their physical transformation, our streets, squares and buildings accumulate history, allowing our surroundings to build up a memory. This way, certain places can be linked with the history of an individual or a community, and therefore have a structuring effect on a mental level. Such a concept of space, loaded with symbolic and semantic values, allows for an associative approach of the built-on surroundings. It is not a matter of physical and aesthetic aspects of the buildings and areas, it is rather about their place and meaning in the collective memory.

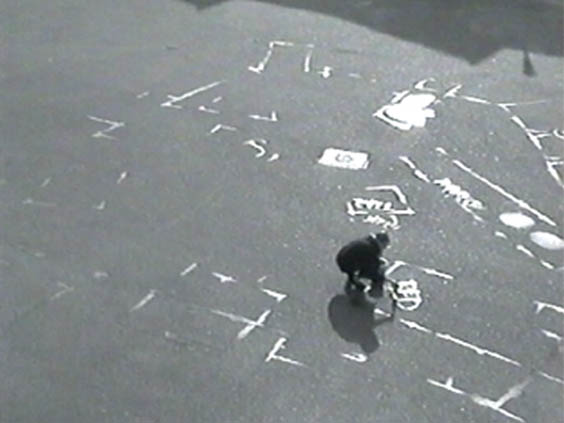

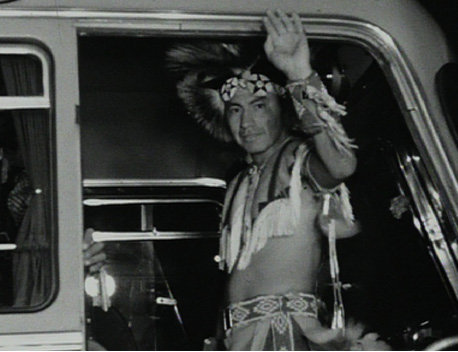

In The History of New York (from the Beginning of the World to the Present) Katleen Vermeir uses this as a theme. In her attempt to expose the historical and semantic layers of New York, she claims the city as her canvas. On certain places in the city she draws in chalk the outlines of former marshes or buildings that where once there. At other times she writes an old place name on the sidewalk. These interventions have the effect of a prism: they refract the obvious and trivial character of a place by relating it to the history of the city and its inhabitants. This way, Vermeir develops a type of archaeology of the memory which invites inhabitants and visitors to a journey in their own imagination. This of course makes for a very thin boundary between reality and fiction; nothing prevents the inhabitant to project his own imagination on certain places and thus build a personal history of the city. This is also the starting point of Cadavre exquis Brusselle part 1. In this film Katleen Vermeir shows an old film director on a walk along Brussels’ former movie theatres and film houses. We also get to see this director’s own house, which he used as a setting for some B-movies and documentaries he made in the seventies. By inserting fragments from this work in the documentary, Vermeir creates a surrealistic unity in which staging and reality each try to claim the truth.

The interference between the present and the past is another theme in the installation Katleen Vermeir now presents in Koraalberg gallery. The starting point is an idea the American artist Gordon Matta-Clark proposed in the seventies, but which was never carried out. The artist wanted to cut a spherical quadrant out of the corner of a ruinous building in Antwerp. In other words, Matta-Clark wanted to suggest the presence of this volume by making the void surrounding it, visible. Out of concern for the public security however, the township gave no authorization for this, forcing Matta-Clark to restrict his intervention to the interior.

By boldly cutting and carving in a building, the artist wanted to expose the architects’ conceit and the deterministic character of their constructions. He did this by literally and figuratively bringing the architecture to its turning moment. By making carefully designed openings Matta-Clark did not only show the spatial and historical layers of the building, he also turned it into a fragile construction which invited you to a spontaneous claim and triggered a new, changed perception of the existing spaces. In her new installation, Katleen Vermeir plays in a similar and complex way with spaces, views and meanings. This should be seen as an interpretation as well as an elaboration of Matta-Clark’s proposal, which was never realized. Here, Vermeir uses all three concepts of space that appeared in her previous work. She intervenes on the building’s shell by cutting – in her mind’s eye - a spherical quadrant from the facade. She suggests the result of this intervention by projecting on the walls of the gallery the variations in the incidence of light and the moving shadows which would be the consequence. Instead of physically intervening on the delimitation of space, Vermeir plays with perception, giving the visitor the feeling that the space is moving around his body. Therefore, the gallery serves temporarily as a kind of observatory to bring a new order into the universe. With her new installation Vermeir finally also addresses Antwerp’s collective memory, by tying in with the turbulent debate about contemporary art in this city during the seventies. The building where the gallery is situated, used to house the NICC (Nieuw Internationaal Cultureel Centrum), an initiative of artists, defending their interests, and which started from a protest against the closing of the ICC, the International Cultural Centre that invited Gordon Matta-Clark to Antwerp in those days. With this installation Katleen Vermeir examines the history of this place, and makes it explicit. She does this quite literally, by showing the layers of the walls, and figuratively, by letting Flor Bex, former director of the ICC and the MUKHA, speak in a video document. This installation resurrects the old controversy around the intervention of Matta-Clark, and therefore inevitably has critical implications; it questions the gallery as an institute. Through this intention, Katleen Vermeir joins the American artist in his polemical attitude towards the artistic circles. But whereas Matta-Clark shows his criticism by means of material deconstruction, Katleen Vermeir uses the suggestive power of the space.

Sven Sterken, November 2005

(translation into English: Anne van doorslaer)