Katleen Vermeir

- AMBULANTE ARCHITECTUUR

- AXIS MUNDI

- BELLE-VUE

- CADAVRE EXQUIS (BRUSSELLE, PART1)

- CIRCUITS

- DIACHRONICAL LANDSCAPE

- FITTING THE PICTURE

- HORTUS CONCLUSUS

- LIQUID ARCHITECTURE

- NO MAN'S LAND

- SEISMOGRAPHIC REGISTRATION OF A BUSRIDE DURING A LANDSCAPE

- TABLEAUX-VIVANTS

- TABLEAUX-VIVANTS (after Vermeer)

- TABLEAUX-VIVANTS (CONSTRUCTION MODELS)

- TABLEAUX-VIVANTS/ CONSTRUCTION (MODELS) #04

- THE HISTORY OF NEW YORK (FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE WORLD TO THE PRESENT)

- THE IDEAL CITY (PORTRAITS)

- THE IDEAL CITY (TWO BOATS)

- THE PASSING OF A PERFECT DAY (for GM-C)

- THE PASSING OF A PERFECT DAY (REVISITED)

- WATERDRAWING

- WHEN DID YOU LAST MOVE YOUR FURNITURE AROUND?

A dialogue with Time and Space, a conversation between equal partners

The question about the meaning, the implications and the nature of time and space has fascinated mankind since ever. It is a philosophical question to which only science has begun to formulate an answer. Between the inadequacy of the scientific answer and the gravity of the philosophical question, art finds its refuge. There it shows its colourful spectrum of propositions and suggestions. It puts the question in a subtle way, apparently and even distinctly without looking for a specific answer, but enjoying the suggestion and the exploration.

Katleen Vermeir has voluntary hurled herself into the vortex of time and space that surrounds her. She has made these concepts her allies. Without ever trying to overpower them, she participates in their game, sometimes whispering, and hardly visible, as in Water Drawing (1999), at other times making a firm and explicit statement, as in The Ideal City (2002).

In 1998 Vermeir makes her debut with Seismographic registration of a bus ride while a landscape. It is a first and resolute meeting between the artist on one hand and time and space on the other hand, crystallized into a work of art. In this early work, Vermeir first seems to strike upon the actual and probing presence of time and space. On a bus ride in far away China and Tibet, she meets time and space as a strange traveller. She will first tolerate this companion, and than gradually get to know him and let herself be carried away with him. Finally she gives him a place through a dialogue.

Seismographic registration of a bus ride while a landscape is a series of ten postcards that originate from the slide of a ballpoint on paper during a bumpy bus ride through parts of China and Tibet. In this work Vermeir lets herself be completely guided and tempted by the power of her partner. Her own contribution, apart from her decision to grant this partner his own monologue –that is, the registration of movements-, is virtually non-existent. The cards can be read as a series of seismographic registrations, fanciful but demonstrating a certain factualness, noncommittal but still very present.

When in 1999 she has her own solo show (Ambulant Architecture) in Netwerk Galerij, Vermeir again seeks the companionship of her partner. In the mazelike structure of the gallery, which was created out of working-class houses, Vermeir reveals the former structure of the housing complex by the use of silk threads. She draws a three-dimensional history of a specific place, abstracting all factualness, in an attempt to bring the impalpable within reach. The observer, who can enter this space the silk threads cut through, now physically participates in the artist’s dialogue with time and space. In this work of art, Vermeir uncovers a part of history that had become invisible. She digs into the past of the place and captures a sense of space that was never experienced before.

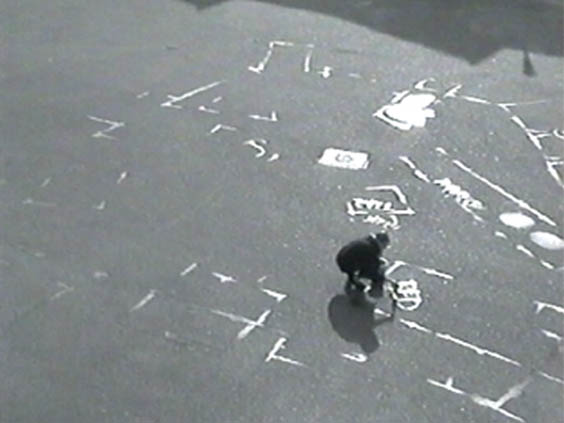

In 2001 Vermeir reaches an important turning point in her work. The artist then introduces her so-called Tableaux Vivants, works in which the landscape (urban as well as rural) is very clearly incorporated and confronted with the human figure. The Tableaux Vivants are video registrations in which time seemingly has been put to a standstill by showing frozen human movements in virtually un stirring landscapes.

They are anonymous sculpture groups that refer to history and at the same time point out timelessness. In addition, Vermeir chose for her first Tableaux Vivants a location that is suffused with that same contradiction: the gardens of the castle of Gaasbeek, a place where history has frozen to a timeless expression. By creating her Tableaux Vivants, Vermeir introduces the human figure into her work. In previous works, the human figure was present in just a few scattered instances, namely in the shape of the artist (as in diachronic landscape), but as an instrument, an accidental presence, rather than a vital part. With her Tableaux Vivants it seems as if Vermeir wants to introduce a point of reference, a standard measure to which time and space as well as their impact could be measured, for the static with their timeless pose and dress seem to be first and foremost the only thing to go by in an ever changing constellation that is the essence of time and space, with nature as its expression. They make out the only tangible references in a constantly changing frame. This is also very present in The Ideal City, a work that Vermeir created during her stay in New York, and that focuses on the cities skyline that has changed so dramatically after September 11, 2001.Vermeir puts her models in their imperturbable poses against a dramatic background. In this confrontation, the human figure is the only element that gives true meaning; its absence would nullify the tragic nature and even make any existence of time or space unthinkable. Fitting the picture, a work she made together with Ronny Heiremans, shows the same susceptibility: two figures pose in the immense, legendary canyons of the southwest (US). They look tiny, but at the same time they alone give a meaning to this landscape, they are the only point of reference to which the immensity of this landscape can be measured. With her Tableaux Vivants Vermeir sets things right, and in her conversation with time and space, she now seems to lay out the rules of the game, giving time and space a distinct place.

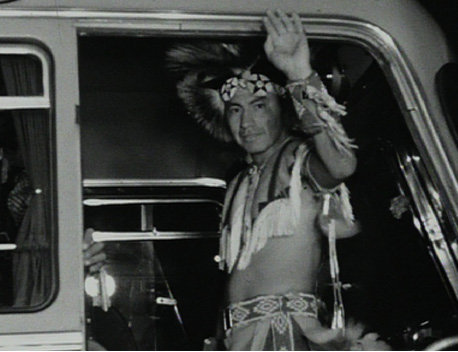

After her experiments with the Tableaux Vivants, Vermeir appears to have commanded and safeguarded the position of mankind within the experience of time and space. In her video film cadavre Exquis,Brusselle, Part 1 (2004), Vermeir shows a human history that is alive, a history in the process of formation. She makes the film about the person of Pierre Querut, a man from Brussels who in the seventies was active as a film producer and film distributor in the Northern district of Brussels. With Querut as her guide and narrator, Vermeir wanders through the city, and lets herself be guided by the hidden, coloured, fragmented history that the filmmaker reveals to her in every detail. She registers the details he points out to her, as well as the technical comments on filmmaking he gives her. Vermeir combines the specific history of Brussels this man shows her, with her own life story (Querut is also her landlord and in the past repeatedly used her house to shoot films in), and with her perception of cinematic registration. This way, several periods and experiences of time and space by these two completely different persons are combined into one moment. It marks the beginning of a new zest in which Katleen Vermeir, through a balanced dialogue and as a worthy conversation partner, further refines the game she plays with time and space, and hereby further reveals and at the same time shrouds the mystery of time and space in an intriguing way. The dialogue leads to a wider spectrum of appreciations and experiences for the observer. Through Querut’s personal story, the clash between the filmmaker and the filmed, and the artist’s personal registration and filming technique, Vermeir now also introduces the narrative element in her work, a notion that leaves room for perspective, humour, and the beauty of the details with their striking anecdotes.

Despite the rapid evolution of her work in a relatively short timeframe, Vermeir appears to have succeeded in maintaining the points of departure she had at the start of her artistic career, in a dialogue that has gradually grown stronger. Therefore, Cadavre Exquis, Brusselle, Part1 at this point can be regarded as a climax, a work that holds the promise of new horizons for the artist to discover.

Els Roelandt 2004