Katleen Vermeir

- AMBULANTE ARCHITECTUUR

- AXIS MUNDI

- BELLE-VUE

- CADAVRE EXQUIS (BRUSSELLE, PART1)

- CIRCUITS

- DIACHRONICAL LANDSCAPE

- FITTING THE PICTURE

- HORTUS CONCLUSUS

- LIQUID ARCHITECTURE

- NO MAN'S LAND

- SEISMOGRAPHIC REGISTRATION OF A BUSRIDE DURING A LANDSCAPE

- TABLEAUX-VIVANTS

- TABLEAUX-VIVANTS (after Vermeer)

- TABLEAUX-VIVANTS (CONSTRUCTION MODELS)

- TABLEAUX-VIVANTS/ CONSTRUCTION (MODELS) #04

- THE HISTORY OF NEW YORK (FROM THE BEGINNING OF THE WORLD TO THE PRESENT)

- THE IDEAL CITY (PORTRAITS)

- THE IDEAL CITY (TWO BOATS)

- THE PASSING OF A PERFECT DAY (for GM-C)

- THE PASSING OF A PERFECT DAY (REVISITED)

- WATERDRAWING

- WHEN DID YOU LAST MOVE YOUR FURNITURE AROUND?

“It is not the office of art to spotlight alternatives, but to resist by its form alone the course of the world which permanently puts a pistol to men’s heads”

- Theodor Adorno

In 2007 the well-known American art critic Jerry Saltz published an article entitled “Has Money Ruined Art?” (1) in New York magazine. It was just before the economic crisis had erupted, at a time when the contemporary art world was in a state of delirious euphoria, when it seemed that almost any old rubbish could be sold for significant – even exorbitant - amounts of money. Then the crisis broke, the hedge fund managers disappeared and the art world began sobering up. In many quarters there was a certain relief and – yes, hope even! - that finally there would be a return to art’s content and substance. A bit more than a year on the art market is slowly bouncing back and all this wishful thinking is becoming a distant echo, since people have short-term memories and art has become too much of an irresistible status symbol for social climbing wannabes.

It would be inutile here to trace the gradual commodification of art, the rise of the commercial art market since the 1960s, and the effects it has had on a large segment of contemporary art in particular. True, today much art is dependent on branding, publicity or marketing, and even artists themselves – not to mention curators - have become brands. One rich man bets on a ‘hot’, emerging artist and the rest seem to follow in sheepish succession, hoping that they will reap big profits as a result. Anyone not willing to jump onto this bandwagon – lets call it the ‘art-system’ - risks being ‘left behind’. For the violence exercised by the market on art is a much more insidious kind of violence, in comparison to the other types of violence that capitalism inflicts on people’s lives in very real, tangible ways. This violence is of an altogether different nature – more metaphorical; and the power it exercises is more ‘conceptual’, dare I say. For it has altered the very nature of art and the way we perceive it. It has turned art from something of cultural value – for want of a better word - an ‘object’ of creativity which cannot be quantified, to a currency to manage, a competitive spectator sport, an object to be possessed as opposed to appreciated and enjoyed, a commodity with stock market value. It has turned artists into the court jesters or pampered, spoiled children of the nouveau riche and has made these latter ‘players’ more important than the artists, who themselves have had to turn into ‘entrepreneurs’. It has resulted in inflation, surplus, superfluousness, superficiality and vacuousness. It has made art more susceptible to ‘naturalism’ a term used by the Hugarian Marxist George Lukács to denote the reliance on surface detail and description, rather than revealing the subject’s inner significance. Lukács considered naturalism to be a degraded form of realism, devoid of narrative capacities and thus limited to mere description. As the American critic and art historian Donald Kuspit suggested in a recent article, we are at a time when it would appear that the art market has usurped the spiritual, aesthetic, cognitive, emotional and moral value of art. (2) It has turned art into something that can be measured - like money - when art is in fact subjective and can’t be measured.

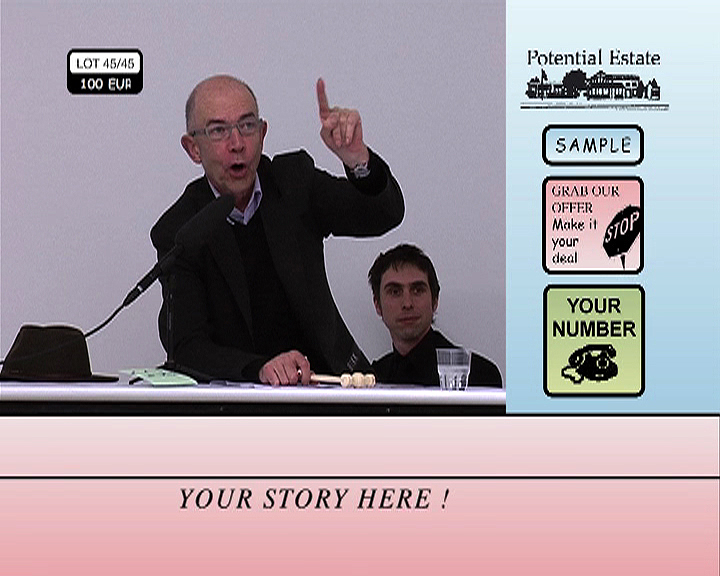

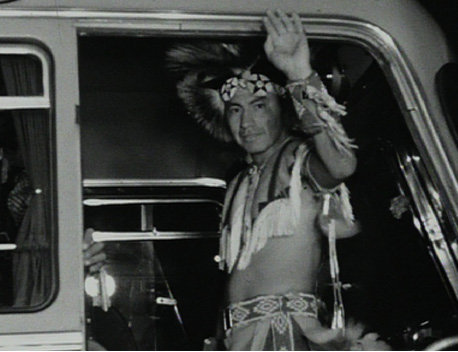

All these issues – and more – are raised in a recent film by Potential Estate, a temporary alliance of artists (3) which operates collaboratively along models of self-organization and participation, often challenging the fixed hierarchies of the art world and turning them on their head. The film, entitled The Crying of Potential Estate (2008) is, in fact, a critique - even fulmination - on the mechanisms of the commercial ‘artworld’ as we currently know it. It depicts an auction that took place in a commercial gallery in Antwerp. A story written collaboratively by Potential Estate was put up for sale. The story was cut up into 45 lots that were read from an audio-booth concealed in the gallery’s basement. A professional auctioneer was hired to conduct the auction in four languages; after each phrase or sentence was read, the bidding started. All lots were sold. The film captures the saleroom atmosphere of anticipation, excitement, and competitive bidding. As the auction progress the story that is gradually being sold off unfolds. It revolves around three characters: The Indian, The Tiny Economist, and Wally Hope. Though the characters retain a certain sense of ambiguity throughout the story – and thus can be afforded a multiplicity of meanings – they can also be seen as potent metaphors for certain aspects of the art market economy and the capitalist ‘ethos’, if we may call it such. Wally Hope – a sadistic, vicious, bloodthirsty, bestial creature, a “filthy animal” with “a bloody mouth, seven tiny brains, and one black heart” is the central character that defines the film’s narrative plot of pre-meditated murder. The story is simple, Wally Hope sets out to annihilate The Indian, a less well-defined, more elusive character who personifies the archetypal ‘Victim’ and can also be read as a metaphor for notions of difference, ‘otherness’ and ultimately frustrated resistance; a character could be seen as representing an alternative to the Status Quo. The Indian is the underdog, he who suffers in the light of Hegemony or coercive power. Wally Hope is also an extreme archetype, who epitomises the greed, and voracious, violent proclivity of ‘The Market’, a Gordon Gekko of hideous physique and even more hideous ‘appetites’. On the other hand, the Tiny Economist, as the title suggests, represents that particular kind of non-entity, a quantité négligeable, a petty bureaucrat; one of the many, obedient, unquestioning facilitating cogs in the wheel of The Market (capitals intended); a narrow-minded, paltry, insignificant figure who does not see behind the trappings of the market and is an uncritical, servile follower of capitalist dictates. The Tiny Economist believes that “the language of economics has come to dominate all aspects of social life” and that “the fusion of art and economics means that there are no values beyond [those of] the market”.

The village of Belgium, Wisconsin presents itself as the utopian location where the story plays out. Though it does sound a bit odd, Belgium, Wisconsin does actually exist (it is located two miles west of Lake Michigan; and has an overwhelmingly white - 96.3% - population of 1,678 according to the 2000 census). It was set up by immigrants from Belgium and Luxembourg in the middle of the nineteenth century. Repeatedly, the film’s narrator reminds us that, “Belgium, Wisconsin is the closest to utopia as one can get”. In the film, Belgium, Wisconsin functions as a symbolic space that questions the crisis of the concept “nation”, and acts out a buffer between our alienating urbanised environment and the idea of community as utopia. At the same time, as the story progresses, however, we find out that Belgium, Wisconsin also comes to represent the corruption of utopian ideals by capital; the fact that ultimately, anything/everything can be bought, even Utopia, ‘it’s just a question of price’, as goes the well-known cynical, capitalist creed.

Eventually, Wally Hope exterminates The Indian, and partners up with The Tiny Economist on a financial venture. They turn the unedited footage of the murder, which has been documented on camera and provided by Wally Hope, into a film that is then distributed commercially. The film, we are told in the conclusion, ends up being screened at the Sundance and Cannes film festivals, but receives poor reviews. Nevertheless, The Tiny Economist manages to invest wisely from the film’s proceeds and with the profits gained he is able to buy Belgium, Wisconsin “the closest thing to Utopia as one can get”. So the village of Belgium, Wisconsin also becomes a contested territory, a site of a new conquest or ‘colonisation’, this time by the victorious, violent forces of Capital.

The public, which plays an integral role in the live auction and hence the film, were initially unaware of their upcoming role as both active participants and film extras when they entered the gallery without knowing what was about to take place. They were also unknowing of their impending roles as potential bidders for an art work, as well as witnesses and accomplices in the bloody plot that unravelled once the auction commenced.

The Crying of Potential Estate contains all the components that are particular to the Potential Estate’s working methods: from open, participatory, collaborative modes of production that challenge traditional notions of ‘authorship’ and artistic ‘signature’, to strategies of oppositional practices and the instigation of alternative economies. In this case, what is sabotaged and subverted are the fundamental principles of the art market and its dependence on the financial exchange of a tangible ‘object’. Potential Estate effectively auctioned off a concept, an idea and not a tangible object. The bidders were bidding for a sentence in a story, not knowing exactly the form or shape of their purchase, but quite possibly assuming that they would receive something slightly tangible, perhaps in the form of a text work – a less desirable but also perfectly marketable variety of contemporary art. And by the end, Potential Estate deliver the final subversive coup: instead of receiving a text fragment, as might be expected, those who placed a successful bid received a signed photo of the story’s narrator - who at the time was concealed in the basement, in direct contact with the auctioneer who repeated the story - with the inscription ‘In Memory of Lot number…”, for each one of the 45 sold lots. So the bidders in fact ‘acquired’ something that was fundamentally conceptual and immaterial in nature for they received but a token of the memory of a narrative, or of the ‘experience’ to use a term increasingly favoured by the current culture industry. And even the token ‘evidence’ that the bidders received for the occasion was not without irony, as the narrator’s portrait resembles a kitschy, radio talk-show host.

In effect, in buying the sentence the successful bidders also signalled is death; the impossibility of it assuming a physical, marketable form, at the same time frustrating its expected potential for it to acquire a certain financial ‘value’ ascribed to it as an ‘artwork’. Thus Potential Estate not only invalidated or negated the fundamental ingredient necessary for the sustenance of the art market: the art object per se, but even deny the possibility that this work may materialise in the shape of an also sellable, but less blatantly ‘commercial’, and thus more artistically ‘legitimate’ form of avant-garde ‘concept art’. And they turned the viewers – complicit in this transaction – into self-sabotaging collectors of next to nothingness, victims of their desire to partake of the ownership process. So the public became implicated in a double murder – that of the orthodoxy of the art market as well as that of the murder which takes place within the story itself.

The Crying of Potential Estate was premiered at the 1st Brussels Biennial in 2008. The conditions under which the film was presented also raise further questions in relation to economic issues as well as those of curatorial practice that underlie the presentation of art, this time in connection with the institutional, publicly funded domain. The Biennial was “an initiative of the Flemish Community” and thus publicly funded by the Flemish Ministry of Culture. Yet, the artists received no fee and minimum support to set up their installation. Being aware of the problematic conditions in relation to this Biennial’s capacity to offer tangible artistic support (one of the responsibilities of such initiatives which should go without saying but unfortunately increasingly don’t) they decided to participate anyway, formulating or rather conceptualising the nature of their participation as a gift, in line with French sociologist Marcel Mauss’ idea of the gift economy. (4) Symbolically, they thus removed any idea of economic transaction from the exchange between artist and institution and laid bare the problematics of such structures, which exploit the position of the artist – and their natural desire to exhibit their work. And this gift would be of a double nature as the film would also subsequently be offered to the village of Belgium, Wisconsin. In order to do this, a collective sale of the copy of the film has been instigated through the hire of an independent ‘Potential Estate Agent’, responsible for seeking out potential buyers-shareholders who are asked to invest in a share of the film (20 shares are offered for 500 euros each). This way the investors – collectors are also asked to disavow their traditional status as signifiers of ownership and become directly implicated in the modus operandi of the gift economy. The village of Belgium, Wisconsin, in reciprocity, has to screen the film once a year in a public place, in acknowledgement of The Gift, which in itself constitutes an auxiliary project, a by-product of the film.

The problematic stance of the Biennial vis a vis the artists also became apparent when the Biennial, facing bankruptcy, asked the participating artists to conceive of ten original art certificates, for the Brussels Biennial to put on sale, with no mention of compensation for the artists. So not only were the artists inadequately supported financially, but they in turn were being asked to support the Biennial itself, in a rather strange twist of events. Potential Estate refused to participate in this process, via an open letter to the Biennial’s board and artistic director which was also published on their website and disseminated as a newsletter. A number of reasons were sited:

“First there is the nature of our presence in this edition of the Brussels Biennial. The original condition of the exhibition space the Biennial assigned to Potential Estate, obliged us to transform it thoroughly, notably at our personal expense. As things are, we find that we already have been very supportive to the Biennial, not only offering the première of our film ‘The Crying of Potential Estate’, but also transforming a greasy technical room, into an intimate lounge situated between two spacious floors in the cold Post Sorting Center….We intend The Gift to raise the complex issue of economic transactions in the field of contemporary art. Basically our project inscribes itself as a rupture into your invitation to support your ’decision to recapitalize the Brussels Biennial to the amount of 285.000 euro’. Questioning your invitation is in our view also questioning the forms of exchange in the art economy at large. Biennials producing art works on condition of their advance sales to collectors or private banks, as was the case for some works in this edition of Manifesta and the Brussels Biennial, seems more a unilateral redistribution of roles rather than a direct consequence of the current worldwide economic crisis….So do we calculate correctly? One third of the Biennial’s total budget will depend on the generosity of its participating artists, and your ability to capitalize on their efforts? Are we being invited to butter the Biennial’s sandwiches, as a bonus?” Finally, they remind the artistic director of the Biennial of one of her fundamental roles: “Is the work of the curator not that of the one who takes care, of the work and consequently of its author?” (5)

It is worth mentioning that Potential Estate’s project for the Biennial, which involved the presentation of the film The Crying of Potential Estate, as well as the set up of a bar and area of social exchange within the same space, was entitled Cabinet Anciaux, a direct reference to the then Flemish Minister of Culture, Bert Anciaux (who was one of the few people who continued to believe in and support the existence of a Biennial in Brussels, despite the early warning signs that all was not well within the ranks of the organising structure of the 1st Brussels Biennial). Anciaux was adamant and systematic in ensuring that it was made clear that the biennial was “an initiative of the Flemish Community” (this sentence was inscribed in all the publicity material, ensuring that the Ministry – and Anciaux, of course - claimed ‘ownership’ of the event. The sentence did ring a tad regional and provincial, especially in the light of the fact that it was attached to what was supposed to be an ‘International Biennial’ with global ambitions). The choice for the title “Cabinet Anciaux” - a reference to Marie-Adèle Anciaux, a 19th century libertarian educationalist - thus proposes a counter-narrative, grounded in social praxis and ideals of welfare (6).

One has to wonder why inherently problematic endeavours such as the 1st Brussels Biennial are even embarked upon in the first place, if they are not able to provide even the basic support that participating artists are rightfully owed. Unfortunately it has become a well-known, if not commonplace fact that Biennials have become more about city marketing (in the case of Brussels Biennial not even this target was realised), tourism, political gains, networking, PR, curatorial vanitas etcaetera, and less and less about art and artists. In fact, the artist now seems to lie somewhere at the bottom of the agenda, as the necessary pawn or ‘apparatus’ which provides a raison d'être or rather the excuse that justifies the event. (Indicatively, I recently logged onto the website of the current Lyon Biennial and the names of the participating artists are nowhere to be found). It is further paradox that while it sometimes appears as if there is a considerable amount of money flying around in the art world, it invariably does not seem to reach the artists themselves. But we are – all art ‘professionals’ – collectively responsible for this state of affairs. Indeed, as a recent study commissioned by Edinburgh College of Art suggests “The time has come for all of us involved in the mediation of art to play an active part in redressing [this] balance…” (7)

On the other hand, however, it could also be argued that artists themselves are legitimising such structures and practices by agreeing to participate in them, for the understandable reason that Biennials as such can provide important platforms of ‘visibility’, for better or for worst as the latter case may be. The same argument could be directed towards Potential Estate themselves, the only difference being that they actually used their participation to raise the highly relevant questions that transpired as a result of the problematic relationship between them and Biennial. Whether this stance effectively changes anything, is another question. And here I do agree with the point made by Miwon Kwon that “artists - no matter how deeply convinced their anti-institutional sentiment or adamant their critique of dominant ideology, are inevitably engaged, self-servingly or with ambivalence, in the process of cultural legitimation”, (8) and that this is an issue that artists themselves need to address more.

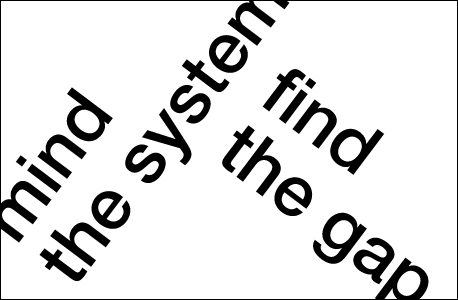

By unexpected and entirely ironic coincidence the dates of the Biennial coincided with the unfolding of the current economic crisis whose roots – even more ironically enough - lie in real estate; that is, in the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the United States. In this light, even the title of the group and the film itself, both acquire an additional level of significance and meaning. No doubt, however, The Crying of Potential Estate is a complex, germane and multi-faceted project as regards the commodification of art, the nature and function of the art market, current institutional practices, and the role of the artist within these frameworks. Perhaps the project’s most important parameter, apart from its function as institutional critique, is its significance as a symbolic act: as a reclamation of the power of the artist to decide how, where and why their work is presented and finally exchanged; and in effect as an attempt to change the hierarchical structure by which artists have to abide through a decisive act which subverts the rules of the art market system. In that sense, it also fits into a trajectory of significant contemporary art works which function as a critique on the art market, challenge the commodification of art, the ‘selling out’ of the artist, and the psychopathology of the market; from Michael Landy’s dramatic destruction of all of his possessions, except the clothes on his back, in an empty department store on Oxford Street, London’s most popular shopping destination (2001), and Andrea Fraser’s Untitled (2003) a video where the artist is seen having sex with an unidentified American collector who paid close to $20,000 to participate in this work of art, to – more recently - Superflex’s The Financial Crisis (Session I-V) [2009]in which the artists treat the current economic crisis as form of psychosis requiring the treatment of a hypnotist.

At the same time, the film’s story can be seen as a potent metaphor for the violence that the market and capitalism exercises on art, a form of violence that plays out in different shapes and forms: from the fact that the market readily ‘consumes’ its own children (young artists) and readily discards them, in voracious anticipation of the next neophyte and product which will also be subsequently consumed, exhausted, and cast aside; to the fact that artists are now latently coerced to churn out artworks that can be readily sold, thus compromising and willingly relinquishing their artistic freedom and integrity. Indeed, as Pierre Bourdieu has argued out in his seminal book The Field of Cultural Production, while artists became autonomous, i.e. free from the demands and constraints of the state and church and able to create what they choose, they at the same time have become subservient to the market, compelled to create work that satisfies the demands of the public in order to sell. (9)

It thus does indeed now appear as if a large segment of art in our post-modern era has relinquished its subversive critical function, as Frederic Jameson pointed out quite early on, in addition to having lost the oppositional character that was inherent to much modernist art. Whereas modernist art often attacked the bourgeois society from which it emerged, the art of the post-modern period largely “replicates…reproduces…[and] reinforces..the logic of consumer capital” (10). As modernism lost its subversive edge and became commodified and assimilated into the art market, the radical social politics it believed in have not been filled by post-modernism. Jameson criticised the status of the artwork as an autonomous object separated from the context of its production and the anti-historical formalism which sever it from this context and from the social-economical realities from which it springs. In that sense, his criticism may also be applied to the current formalist return in much contemporary art practice, which – unsurprisingly – is also commercially fashionable. Pierre Bourdieu calls this kind of art l’ art moyen or ‘middle brow art’, art which appeals to popular taste and offers some promise of financial profit.

Slavoj Žižek goes on to talk about how the problem regarding the functioning of today’s artistic scene “is not only the much-deplored commodification of culture (art objects produced for the market) but also the less noted but perhaps even more crucial opposite movement: the growing ‘culturalisation’ of the market economy itself. With the shift towards the tertiary economy (services, cultural goods) culture is less and less a specific sphere exempted from the market and more and more not just one of the spheres of the market, but its central component (from the software amusement industry to other media productions). What this short-circuit between market and culture entails is the waning of the old modernist avant-garde logic of provocation of shocking the establishment. Today more and more, the cultural-economic apparatus itself, in order to reproduce itself in competitive market conditions, has not only to tolerate but directly to provoke stronger shocking effects and products”. (11) There are examples galore of this kind of highly-sellable shock-value contemporary art from – more obviously - Damien Hirst and other ‘bad boy’ artists to Andres Serrano, and beyond. Žižek goes on to say that “perhaps this is one possible definitions of post-modern as opposed to modernist art: in modernism the transgressive excess loses its shock value and is fully integrated into the established art market” (12).

Nonetheless, it is easy and at the same simplistic to demonise the role that capital plays in the art world. Money - from the time of the Medicis - has always been implicated in art and has invested in art, which it perceived to be a superior force; (the difference being that perhaps back then people were more aware of the dialectical varieties of critical consciousness that art proffers and could better genuinely appreciate art itself). So the question is not how to eliminate money from the equation as artists also have to make a living but how the conditions for art production can be less dependent on the art market and its rules – rules that affect the nature of the art that is being produced; in effect, how it is possible for artists to conceive of strategies or practices for what Dave Hickey called “selling without selling out” (13). He adds, and I agree, that “there has never been a better chance to call attention to oneself by behaving honourably” (14).

Its realistic not to forget that ‘the market’ also affords many artists a living when they would probably be having a hard time making ends meet (and here I don’t refer to the very few multi-millionaire artists like Damien Hirst but those that make modest and decent livings). The problem is not the free market per se but that money has become more important than art, much in the same way that Pierre Boudieu described the transformation of the economy from being a ‘thing in itself’ into a ‘thing for itself’. As one critic recently pointed out, “money no longer serves and supports art, art serves and supports money” (15). That this has a limiting effect on creative freedom and the power of art in this respect is obvious. When you are making art with the exclusive goal of selling it, content is clearly compromised (think of the emergence of a recent phenomenon, ‘art fair’ art – i.e. art of doubtful ‘quality’ or substance, made especially so it can be sold at art fairs).

However, all is not gloom and doom. The free conditions under which artists operate in a capitalist system are also a stimulus to creativity. Yes, the big money has taken over art but that is assuming there is only one art world and only one kind of art or artist. But thankfully there isn’t. With contemporary art’s massive publicity machine we often tend to forget that there are many ‘art worlds’ outside the Christies’, Sothebys’, Guggenheims and Tates, ‘art worlds’ and artists that don’t come with a price tag, are not dependent on the market and indeed not interested in being a part of it.

There are many artists who exist outside the commercial art system, supported by public funds or who are making art in economical, creative ways - subsisting by holding teaching or other jobs - whose work is shown by dedicated, genuinely interested people in institutional and non-institutional places from biennials and museums to non-profit spaces. These are the artists who might give back what Bourdieu has called art’s ethical and political dimension, or who may respond to Jean Baudrillard’s call for a ‘new collective symbolic order’. Indeed one of the paradoxes of today is that though there is an unprecedented interest in contemporary art, the position of the artist has never been more disempowered, rendering the artists, in effect, isolated and “when artists are isolated, as they are today, they lapse into clichés and naturalism” (16). Indeed it is a valid and perplexing question that Scottish artist Nick Evans poses when he asks “Why is it that whilst the world outside spirals in ever tighter circles of terror and repression, and the potential avenues of avoidance or resistance become squeezed by the growing dominance of capital and its civil and military bulldogs, artists retreat further into a hermetic world of abstraction, formalism, deferred meanings and latent spiritualism?” (17), in an attempt to try and make sense of the recent turn to formalism, that particularly socially apathetic aspect of art practice.

Nonetheless, there are artists who manage to get by without participating in the gallery system and selling to the big collectors and who occupy their own niche and have their own audience. In fact, the artists whose names are endlessly repeated and hyped by the media constitute such a small fraction, that they cannot possibly be indicative of art practice today. And let’s not forget that we are witnessing a moment of extraordinary creativity in the artistic field – aided and abetted by the emergence of video, digital technologies, open source networks and multi-disciplinary practices. There are so many different ideas coming from so many places that the ‘art world’ has also never been a richer place. The explosion of contemporary art in recent years has also had its good points, in the form of numerous venues and occasions to see good things in perhaps less visible and glamorous venues but ones where there is more content. In any case, art that is served up for immediate consumption is probably art that is not worth pondering over.

So perhaps its time to turn the gaze away from the flashy galleries and that brand of increasingly corporatised museum – counting its visitor numbers and shop profits – to more modest venues. And perhaps it also time for artists to reclaim the power they have relinquished to collectors, museums and curators and to start deciding where, how and why their work is shown. It is also time for them to begin participating more actively in the public life, reclaiming their public voice for they are the most independent and thus appropriate voices of dissent, and as such can be said to represent the conscience of our culture. In that sense, Pierre Boudieu’s utopic call for an Internationale of Artists and Intellectuals who can aim to advance the project of the Enlightenment seems all the more relevant now, “Intellectuals and all others who care about the good of humanity, should re-establish a utopian thought

with scientific backing” (18). Similarly pertinent are Jean-François Lyotard’s ideas about the “pernicious and dehumanising character of capital and thus the importance of an active avant garde to combat the worst effects of commodification (19)

We are now more than ever in need of a critical, opinionated, engaged, independent art infused with genuine concern and sentiment, not just academic musings on reality and arms-length theoretical engagement, protected by the safe, self-contented bubble that is the art world. Raymond Williams and other writers have noted how modern art developed in self-conscious opposition to capitalism. “While capitalism looked at the world from the point of view of mechanical utility, art aspired to be a sphere of ‘imaginative truth’. While capitalism weighs all things in terms of market value, art looks at the object from its many angles. In his 1844 manuscripts, Karl Marx wrote: ‘the dealer in minerals sees only the mercantile value but not the beauty and the unique nature of the mineral – he has no mineralogical sense.’ ” (20). Unfortunately, in certain instances, it would appear that art has also been reduced to the same kind of equation; it’s thus time to wrest back art’s capacity for ‘imaginative truth’.

Art can and should help to expose social reality, and to help facilitate a common humane culture, as an autonomous cultural entity, though that is of course not its only function. Likewise institutions should re-claim their intellectual autonomy and resist playing into the hands of rich patrons, trustees, the market, and mass media. It is sad to see institutions that possessed true artistic vision and were genuine voices of dissent like, for example the Serpentine Gallery in London and the New Museum in New York, bowing to the pressures of the market, the media and fashion and adopting blatantly mainstream, in line with what is currently trendy. “In the light of diminishing and instrumentalised public funding and a massive orientation towards the market, a contingency urgently needs to be developed. A self-sustaining economy that does not rely on the mechanisms of capitalism will be needed to create the conditions for truly autonomous artistic production to thrive” (21). Similarly even galleries can also play a role in ameliorating the situation if they for example showed work they genuinely stood behind, which might engender collectors to ameliorate their views on art. Many things can still be done to curb the shameless capitalism that has infected practically every aspect of our lives. That said, there are alternatives to ‘big market’ art. It only takes a little bit of effort to find them. And that’s another aspect of the ‘violence’ exercised by the market on art – it has made us lazy and less curious. We approach art as if we were sitting on a couch waiting for the cheap thrills of the next episode of the soap opera, or the instant vacuous gratification of the next issue of the gossip magazine. Seek and ye shall find.

Katerina Gregos

Footnotes

1. http://nymag.com/arts/art/season2007/38981/

2. Kuspit, Donald, “Art Values or Money Values”

www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/kuspit3-6-07.asp

The text is derived from a talk titled "Art Values or Money values: An Analysis of Art Prices in 2006," given at the New York Studio School on Feb. 22, 2007.

3. Potential Estate / Cabinet Anciaux is David Evrard, Ronny Heiremans, Pierre Huyghebaert, Vincent Meessen, Katleen Vermeir

The Crying of Potential Estate includes the artistic collaboration of Adam Leech, Mon Bernaets, Amir Borenstein, Eric Thielemans, Jean-Yves Evrard, John Pirard & Marc Lacroix

4. In The Gift, Mauss argued that gifts are never "free" but rather give rise to a sentiment of obligatory reciprocal exchange. The question that drove his inquiry into the anthropology of the gift was: "What power resides in the object given that causes its recipient to pay it back?" (1990:3). The answer is simple: the gift is a "total prestation", imbued with "spiritual mechanisms", engaging the honour of both giver and receiver. Because of this bond between giver and gift, the act of giving creates a social bond with an obligation to reciprocate on part of the recipient.

It is the fact that the identity of the giver is invariably bound up with the object given that causes the gift to have a power which compels the recipient to reciprocate. Because gifts are inalienable they must be returned; the act of giving creates a gift-debt that has to be repaid. Gift exchange therefore leads to a mutual interdependence between giver and receiver. According to Mauss, the "free" gift that is not returned is a contradiction because it cannot create social ties. Following the Durkheimian quest for understanding social cohesion through the concept of solidarity, Mauss's argument is that solidarity is achieved through the social bonds created by gift exchange.

Mauss, M. 1990 (1922). The Gift: forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies. London: Routledge.

5. www.potentialestate.org/Newsletter-02-Curare-Curare.html

6. Footnote: Cabinet Anciaux is named after Marie-Adèle Anciaux (1887-1983) also known as Mary Smiles. Anciaux was a libertarian who participated at early pedagogical experiments along with her husband Stephen Mac Say (1883-1972) teacher, beekeeper, stallholder and author. In 1928, Mac Say published From Fourier to Godin the first complete survey on Godin’s Familistère, the only successful and long lasting utopian community based on Fourier’s communalist theories. The Familistère located in Northern France was a philosophical, social and architectural utopia that lasted a century. Fourier’s writings about turning work into play influenced the young Karl Marx, a former Brussels resident. From: www.potentialestate.org

7. “False Economies: Time to Take Stock”, Curating Critique Reader, Commissioned by Edinburgh College of Art, 2005.

www.shiftyparadigms.org/false_economies.htm

8. Kwon, Miwon “One Place After Another: Notes on Site-Specificity”, October, no. 80, spring 1997, p. 98,